“Let’s dance together!”

Q:You have commented that you wouldn’t be who you are today if you hadn’t met The Otoasobi Project. However, you also admitted that you initially thought it would be a hassle to work with people with disabilities.

Otomo: At first, that’s what I thought. But in hindsight, many musicians are equally difficult to work with and I imagine I am too, so it’s not something I can say particularly about people with disabilities. It all started when a graduate student at Kobe University asked me to take part in her project. She was researching musical therapy for children with disabilities and thought that the music these children made sounded similar to improvised music. Her idea was to pair the two together through a series of workshops.

After I played a show in Kobe, four young women came up to me. They had a proposal in their hands and said: “We are planning something like this. Would you like to join? Arima Onsen (Arima Hot Springs) is nearby, so we can go there afterwards!” I agreed on the spot without even reading the proposal. I was later told that one of them was just there to make the offer more enticing and wasn’t even involved in the workshop! Of course, I still haven’t been to Arima Onsen to this day. [Laugh]

When I read the proposal, my initial reaction was to turn down the offer. It wasn’t so much about working with these kids, but more about the commitment. The workshops were on Sundays, and for me to commute to Kobe several times a month on the weekend would make it difficult to continue my other work.

Q:Had you previously worked with people with disabilities?

Otomo : No. I probably was prejudiced because I had never interacted with people with disabilities and didn’t know what to expect. I went to the workshop to turn down the offer in person, but ended up getting into a huge argument with the instructor of the workshop that day.

In that workshop, the instructor was engaged in various activities with the children. They would pick up an instrument and make sounds, but also would run around playing tag or draw something on paper. It seemed like everyone was having fun. I was wondering while I watched with the parents when they were going to play music, but then the workshop was done. The instructor came up to us and asked, “Did you hear many kinds of sounds?” I replied, “Yes, it sounded like a lot of fun.” Then he said, “That was music!” This rubbed me the wrong way.

I thought we were there to make music with children, not to “discover” music in the sounds they make. Looking back, the instructor probably had intentions of making music with the kids. But his John Cage-like comment, “Music is everywhere” somehow ticked me off. I responded, “Then why don’t we just listen to a flickering light and appreciate its ‘music’!” Our discussion escalated into an argument, and we ended up accusing each other of being disrespectful. I became so frustrated that I wanted to prove that I could do a better job.

Q: In the end, that argument made you commit. Maybe that was their plan all along.

Otomo: That could be true. [Laugh] Although, I was just frustrated at this point, and hadn’t made up my mind yet.

Q:Were you doubtful that you could make something musically interesting with this group?

Otomo : To be honest, I was very doubtful after experiencing the first workshop. . Maybe I was just too upset. This changed when I visited the second time, which was led by improvising musician CHINO Shuichi. They were carelessly doing things, but I could hear many fragments of music popping up here and there. Each one of these small pieces were very interesting and I was intrigued, even though I was still grumpy. [Laugh]

Q:What made you fully commit?

Otomo : There was a high school student at the workshop named NAGAI Takafumi, who was very outgoing and an excellent dancer. He was the leader of the group. Afterwards, Takafumi came up to me and said, “You should dance with us next time. Let’s dance together!” No one has ever asked me to dance with them, and here was a teenager that I just met, talking to me like I was his friend. These kinds of things make me really soft. It’s Takafumi’s words that were the decisive factor for me.

NAGAI Takafumi on the drums with Otomo at KAVC Music Line “STATION” vol.5 “OTOMO Yoshihide and The Otoasobi Project” at Kobe Art Village Center, October 21, 2018. (Photo by KUROIWA Kana)

Working in the dark, but a familiar challenge

Q:Were you able to establish a working method with the group right away?

Otomo : Not really. I became seriously involved with the workshops in January of2006, and it was a genuine struggle at the beginning. I even had moments of regret, but of course I didn’t show this.

When I work with amateur musicians, I use simple hand signs to guide the improvisation. However, with The Otoasobi Project, no one responded to my conduction methods by playing their instruments. I wasn’t sure how much they understood me through words. At one point I told them: “Be free! Do what you want!” Then everyone just disappeared from the room. [Laugh] The first month I was mostly in the dark, failing to make anything happen with these kids.

Q:I suppose no one expects the performers to leave the stage when they are told to be “free.”

Otomo : That’s why I had to ask myself, “What does it mean to play ‘free’?” If we take “free” for its literal meaning, it should be completely acceptable that someone leaves the stage. Instead, Ididn’t accept this, and considered my attempt a failure. Why was my understanding of “free” not relevant here? The children here were already “free” but in a way that was not compatible with society. This was perceived as their “disability.”

It means that even when we are told “do what you want,” there is an unsaid rule or a consensus on what is acceptable behavior. The word “free” applies to only people that can embrace this. I suppose these people are what we consider “abled.” I first had to confront these unconscious biases within me.

This reminded me of when I play overseas with musicians that I meet for the first time. In Japan, I am normally working under the assumption that everyone speaks Japanese and shares the same cultural background. Practical communication is not a problem. However, when I work abroad, I have been in situations where there was no common language between the participants. I would have to start from scratch on how I can communicate through various means. In this workshop, it felt like I was facing similar challenges.

KAVC Music Line “STATION” vol.5 “OTOMO Yoshihide and The Otoasobi Project” at Kobe Art Village Center, October 21, 2018. (Photo by KUROIWA Kana)

Changing perspectives on the “stage” for music-making that is accessible to everyone.

Q:So it became similar to when you make music with people from different cultural backgrounds?

Otomo : Yes, it made it easier for me to think that way and not make assumptions. Everyone in the workshop was so different that it was like visiting a multiethnic country.

The range of what each member could do was also very broad. Some could do everything, while others needed help to move around or understand the conversation. Once I recognized this diversity, I enjoyed discovering how each member was unique.

For example, when I use the microphone to talk, one-third of the children are looking towards the loud speakers next to me. Usually everyone looks at the person with the microphone and not the PA system, even though that’s where the actual sound is coming from. This is because our brain is tricking us, or rather making unconscious adjustments for us to match the sound with the person speaking. It’s the same when we go to a concert and everyone is facing the singer and not the speakers, except for the PA engineer. For everyone else, their brain is telling them that the sound is coming from the singer. That’s typically how we perceive sound.

However, some children can’t do this. They hear things much more precisely than others and this can present difficulties in their daily life. While I have to be mindful of this aspect, I saw this as a special ability that many of us lack. It was a uniqueness that was on a different level than culture or ethnicity. I found this very fascinating.

Q:What was interesting about making music with this group?

Otomo : Everything sounded fresh because it was a rare experience for me to make music with such a diverse group of people. When I am leading professional musicians, I try to work with elements that are beyond my control, but here “controlling” was not even an option that I had. The notion itself was pointless.

The more we played together, it became apparent that each child responded in their own way, which was not always immediate. Their actions initially seemed unintentional and uncontrolled, but this was because I didn’t understand them well enough. They each had their own set of rules on how they responded.

It’s like when simple things don’t go as expected and we think there is an obstruction* in our path. However, in these situations, the only way to move forward is to change our perspective.

There were various hurdles popping up every time we tried to play together. It was like no matter how we setup the stage, it was too steep for some to climb. We had to think of alternative ways for the music-making to be accessible for everyone. This involved changing our perspective on the “stage” and rethinking how it could be set up differently. We had to flex our imagination and think about possibilities of multiple stages in a space or selectable stages by the performers.

For the first couple of months, we tried to figure these things out together with the members of The Otoasobi Project. I really enjoyed this process and found myself looking forward to every meeting.

obstruction*

The Japanese word for disability is “shogai,” which literally translates to “obstruction.”

Finding something in common outside of music

Q:What was your biggest take from these trials and errors?

Otomo : My biggest take was that, in order to play together, it was key to find a pretext that everyone can relate to. The challenge was to make music with members that didn’t share a common musical language. To make this possible, we had to search for something that was outside of the music.

What I mean by this is that we tried to create an environment that made everyone want to play. We started from lining up chairs and building a raised stage in the workshop space. When stage lights were available, we lit the space like it was a real concert. Usually at these workshops, the participants’ parents and other bystanders are standing in the back and chatting. This time we asked them to sit in the chairs quietly and watch the children perform. When the performance was done, we had everyone in the audience give a generous applause.

This drastically changed things, because it became clear for the children who they were performing for. Of course, it was not everyone, but some got the hang of what it’s like to be on stage. Without us telling them to do so, they bowed and even engaged with the audience like a MC. What was most impressive was that the music didn’t drag on anymore. It would end on its own.

Q:That is very interesting how the performers’ awareness changed with the environment. It’s almost like setting up a ritual.

Otomo : Until then, it was difficult for the children to conclude their own performances. It would either end by chance or we had to stop it by telling them that the next group was waiting. This was an issue that we were all trying to solve, but once the children realized that there was a round of applause at the end, many of them made an effort to stop playing.

It must have felt good for them. One of the first sounds that babies make is clapping. This is an “I’m doing something together with you” kind of gesture and they only do it when they feel happy. It’s probably the origin of why we applaud. I am convinced that clapping hands and dancing are driven by the same impulse as music. Everyone feels joy when they are applauded, don’t they?

That’s why the stage and the audience can become the pretext that brings everyone together. You can hear the members saying, “How is everyone? Can we get some more energy?” at the beginning of the second disk of our CD. Maybe they’re just copying something they saw on TV, but it shows how they are embracing the role of the performer on stage.

They probably have watched on TV their favorite idols performing in concerts. We could establish a common ground because they all draw from these fragments of cultural experiences stored in their memories. The fundamental difference between us and these children is that they make different associations even when we think we are referencing the same Japanese culture. In order to understand how they are relating to what is happening around them, we need to observe carefully.

KAVC Music Line “STATION” vol.5 “Otomo Yoshihide and The Otoasobi Project” at Kobe Art Village Center, October 21, 2018. (Photo by Kana Kuroiwa)

A precious moment where sounds are sparkling

Q:Did your “prejudice” towards people with disabilities change as it went along?

Otomo : Yes, I would say I loosened up over time, and my preconceptions disappeared. Maybe it’s like when we first encountered people from abroad. You just have to get used to it. Back in the 90s, when I visited a rural mountain area in Italy, everyone stared at me. There were no Asians in that town and I was a complete outsider. I think the stares came from unfamiliarity rather than being prejudiced.

I was even nervous when I first interacted with foreigners. I didn’t know what to do because I couldn’t speak their language. But once I got used to it, it wasn’t a big deal. From my experience, you can overcome prejudice if you spend enough time together. Of course, the matter is not that simple, but I believe that getting used to each other is an excellent remedy.

It was like that for everyone at The Otoasobi Project. After each meeting, we got used to each other and became closer. It wasn’t just between me, but within the group as well. The music felt stiff at the beginning because they were still shy. This changed as they got to know each other better. For some, like Takafumi, it was immediate. For others, like FUJIMOTO Masaru who plays the trombone, it took months. At first, Masaru didn’t play in front of anyone and just played the piano after everyone left. Eventually he was comfortable enough to play the trumpet and trombone with other members.

At the beginning, some children seemed irritated or stressed. They sounded frustrated when they played, and some even destroyed their instruments. After getting comfortable with each other, you could hear the change in their sounds.

Q:The relationships between members had an influence on the sound?

Otomo : Yes, it was really important. Without using words, there was a lot we understood about each other through sounds. We could tell when someone was in a bad mood from how they sounded. This kind of relationship was new to me and very interesting.

I don’t think of my music in terms of communication, but I felt I could communicate with the members of The Otoasobi Project much better through playing music than using words.

Q: In your book “Gakko Dewa Oshietekurenai Ongaku (Music that is not taught in school)” you describe your experience as, “cherishing every single sound that was sparkling at every moment.”

Otomo : Working with The Otoasobi Project made me realize that improvising musicians like myself, are always intentionally improvising. In comparison, their sounds come out much more naturally. Even with elementary school kids it doesn’t sound this way because they are already learning about music. Learning how to play “do re mi fa so la ti do” is like learning techniques of perspective in painting. When an established painter sees a child’s drawing and says it’s fantastic, typically they are impressed about the lack of intentionality. For example, lines bleeding outside of the paper with no intentions to create the illusion of depth.

I didn’t think such things were possible in music, but The Otoasobi Project was exactly like a child’s painting. There were no ambitions to play “well.” Every moment was just about making sounds and having fun. I thought this was so precious.

We arrived at an idealistic place where we just had fun making sounds. Eventually this became the “normal” way to play music for us.

Q:Did members have conversations through sounds that influenced the dynamics of the music?

Otomo : Of course they did, but it’s not like typical improvised music where they can respond to each other with the same kind of sounds. You understand overtime that everyone is listening and that they are responding on a deeper level. It’s sometimes hard to tell, because the response may not be through sounds. There are even times when they respond by just being there, which I believe is a sophisticated form of communication. The music became much more relaxed after some of their responses could be interpreted as: “I’m just going to be here because I want to” or “you can join in, if you want.”

This was the same for me too. After several months of spending time together, I would just “be there.” I was content just to be in the same space with them. I started looking forward to being at every workshop from around this time because it felt like a utopia. They didn’t take me to Arima Onsen, but this was much better.

As the workshops progressed, we arrived at an idealistic place where we just had fun making sounds. Eventually this became the “normal” way to play music for us.

Q:What a nice way to make music.

Otomo : When I first became involved with The Otoasobi Project, I visited some concerts by people with disabilities to find out what kind of music they were playing. In most cases, it was covers of popular songs. They were doing their best to play the songs, and it looked like they were enjoying it. However, deep down I felt uncomfortable because it seemed like they were trying to prove that they could play regular songs just like “normal” people.

Even at The Otoasobi Project, some parents would ask me, “Why don’t you play normal songs?” I didn’t have an appropriate answer for this, because it actually didn’t matter what songs we played. I told them that I was resistant to the idea of trying to play “normal.”

Q:How did the parents react to this?

Otomo : They said that people already consider their children to be not normal. They were concerned that if their children played my kind of music, people would see them that way even more. To a certain degree, I could understand why they thought my music wasn’t normal, but what does “normal” mean? I felt a bit of resentment because I don’t think what I do in music is not normal at all!

Although, these parents did change their views eventually.

KAVC Music Line “STATION” vol.5 “OTOMO Yoshihide and The Otoasobi Project” at Kobe Art Village Center, October 21, 2018. (Photo by KUROIWA Kana)

We learn to be “normal”, but there should be places where we don’t need to conform.

Q:The definition of “normal” seems to vary between different groups of people.

Otomo : I think people actually mean sociability when they say “normal.” Of course, everyone has their own opinion of what “normal” is, but I still think most people are referring to how much one adapts to the social norm.

When you look at kids around first grade, they are not “normal” at all. They are very unique. Parents and teachers teach them how to be “normal” because eventually they need to become members of society. By being told things like, “You have to behave when you are in public” they learn how to be sociable. I understand that this is necessary, but I feel that The Otoasobi Project could be a place where they don’t have to learn how to conform. That’s why I don’t want to force them to play songs the “normal” way.

Q:Would you say the more we learn the more we aspire to be “normal”?

Otomo : Children over a certain age are often more resistant than adults to trying things that are unusual. They understand that being “normal” pleases adults and makes it easier for them to get along with their peers at school. Of course, there are children who struggle to be “normal.” Although these children are not diagnosed with learning disorders and are “normal” in their own way, they grow up to be called weird or different. Often, art and music becomes a comfortable place for them. In art and music you are praised for how different you are, and being “normal” is equal to being “boring.”

But compared being different in art and music, what takes place at The Otoasobi Project is on another level. So many unexpected and interesting things happen that any kind of comparison feels irrelevant. They are so unpredictable that I am constantly saying, “That’s what you are going to do next?”

Q:You have mentioned that when you started playing with The Otoasobi Project, you couldn’t stand the sounds that you were making yourself.

Otomo : When I reacted to what they do with techniques that I normally use on my instrument, it sounded really pretentious. This made me lose confidence in my playing.

I rarely have this feeling when I am playing with professional musicians. Only when I play with some of the best improvisers in the world is when I feel my sounds are too intentional and not coming out naturally. With The Otoasobi Project, I felt this every time! This was really hard for me at first, but I got used to it. It became a “normal” thing for me. I realized that when playing with this group, better results followed when I abandoned my desires to play well.

KAVC Music Line “STATION” vol.5 “OTOMO Yoshihide and The Otoasobi Project” at Kobe Art Village Center, October 21, 2018. (Photo by KUROIWA Kana)

“OTO” — A dazzling sound world with hints of punk, progressive rock and dub

Q:You don’t seem to hold back on your guitar playing in their new album titled “OTO”, which you produced.

Otomo : Trying to match them or play like them turned out to be unnatural as well. My approach recently is to just play as me, and that’s what you hear in this album.

Q:Why did you decide to record their first studio album?

Otomo : I wanted a better sounding recording of our music. We have recordings of our live concerts, but there is always a lot of noise from the stage and audience, and it didn’t capture the more delicate stuff. I was also curious if this music would appeal to a broader audience if it had a Hi-Fi sound and was packaged with a nice cover design like my other projects.

I first thought we should record in a recording studio, but it’s difficult, especially for members living with autism, to play in a space that they are not used to. Instead, we used the Guggenheim House in Kobe, which everyone was familiar with from playing concerts there. We put up futon mattresses to soundproof the rooms and brought in professional grade audio equipment to transform the space into a makeshift sound studio. We hired professional sound engineers to make the recordings. “OTO” ended up being a double CD album with 48 tracks, but we recorded about 10 times as much material.

Q:The first CD includes recordings of solos and duos, and the second CD is with ensembles and bands. The music was a dazzling sound world with hints of many musical styles, like New York punk, German avant-garde progressive rock, dub, and experimental choir music.

Otomo : Thank you. I hope that each person who listens to this album can interpret it freely.

During these 16 years, I have seen so many formations within the group giving birth to various kinds of music that are impossible to describe through musical genres. These groupings and the music come and go. Therefore, the music included in this album is just something that happened to come out of the group during this period.

One thing that was unfortunate, was that the recording took place during the pandemic. This prevented us from recording a large ensemble. Usually when we play concerts, towards the end we form a big band and Takafumi or MIYOSHI Yuka take on the role of the conductor. This became part of our regular program. When you hear the sound, you immediately recognize a unique The Otoasobi Project rock and roll sound.

I don’t expect anyone to understand, but I think they sound as cool as The Rolling Stones! My one regret for this album is that we couldn’t capture this.

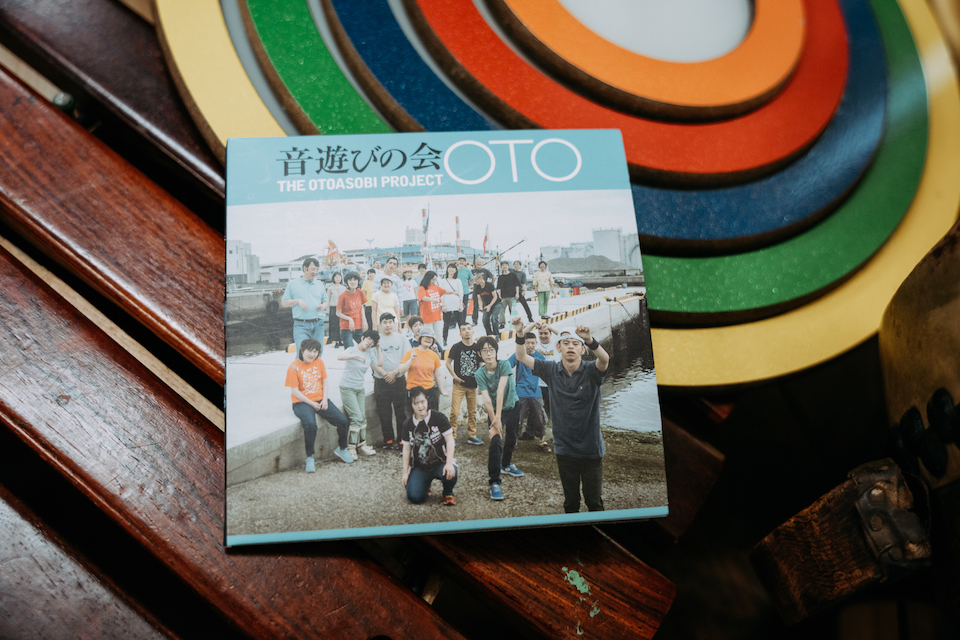

“OTO” (F.M.N. Sound Factory) is The Otoasobi Project’s first studio recorded album since they formed 16 years ago. Produced by OTOMO Yoshihide, the 2 CD album with 48 tracks is divided into “solos & duos” and “band & ensemble.” The album portrays The Otoasobi Project’s unique sound. The CD can be purchased at The Otoasobi Project’s web shop: https://otoasobi.base.shop/

Q:How did the parents change in the end?

Otomo : They changed a lot! The parents that asked me why we weren’t playing “normal” music ended up performing on stage as the “Parents Band” at one of our concerts. I asked them to think of what they would want to do, and they came up with an idea to do a “Vacuum Cleaner Ensemble.” I was so surprised that the parents were even more out there than us! They brought in several vacuum cleaners and played with the sounds that the machines made. After that, they never mentioned about playing “normal” music again.

The parents probably thought about what this improvised music was that their children were playing. This leads to questioning the ideas of music itself. We were all involved in this together. As a result, many things changed. We all became very open-minded.

Q:During your time with The Otoasobi Project, did you also have to question what “music” is?

Otomo : Yes, I had to think about this really hard. I still don’t have an answer. Just more questions like, “When does something that is not music become music?” and “Who and what is deciding this?”

I’m realizing that this involves not only sounds but how to set up the stage, the lightings, and the audience reactions.

This resonates with how we relate to our society. Perhaps our aspirations for an ideal society can be realized in the music we make. I feel The Otoasobi Project is a space where I can do this.

Q:You have also mentioned that you don’t think that some people are “better” at music than others.

Otomo : I believe that there are people “better” than others in music because we assume there is an ideal outcome that needs to be achieved in music. If we stop focusing on the outcome, no one is “better” or “worse.”

For example, if we were to play a game of rock-paper-scissors, but get rid of the win/lose aspect and just focus on the rhythm and tempo, then it becomes an ensemble performing a kind of music. I think the idea of being “better” or “worse” comes from being too fixated on the outcome which is not always the most important thing in music.

Q:Does that mean anyone can be “free” when they play music?

Otomo : I try not to use the word “free” anymore. We often stop thinking when we hear the word “free” and narrow down the definition to only apply to people who can be “free.” Typically, it’s those who are experienced and skilled that are able to play “free.”

Of course, “freedom” is very important in our society and something that we have to cherish.

But for the music that we are trying to achieve with The Otoasobi Project, we have to first think of how to equally share space and opportunities. How can we establish a fair relationship with everyone? The idea of being “fair” is more important than being “free” — This is what I have come to realize through working with The Otoasobi Project.