Art as a Way of Life, in the Center of the Everyday

A long time ago, in a time when there was no such thing as an occupation, everyone danced, sang, and created. Art, as an everyday activity, existed at the center of people’s lives. The word “art,” in fact, is derived from the Latin word “ars,” meaning “way” or “talent.” For the people of that time, art was, without a doubt, a way of life. With the progress of civilization and the division of people into occupations and roles, for most people art receded from everyday life.

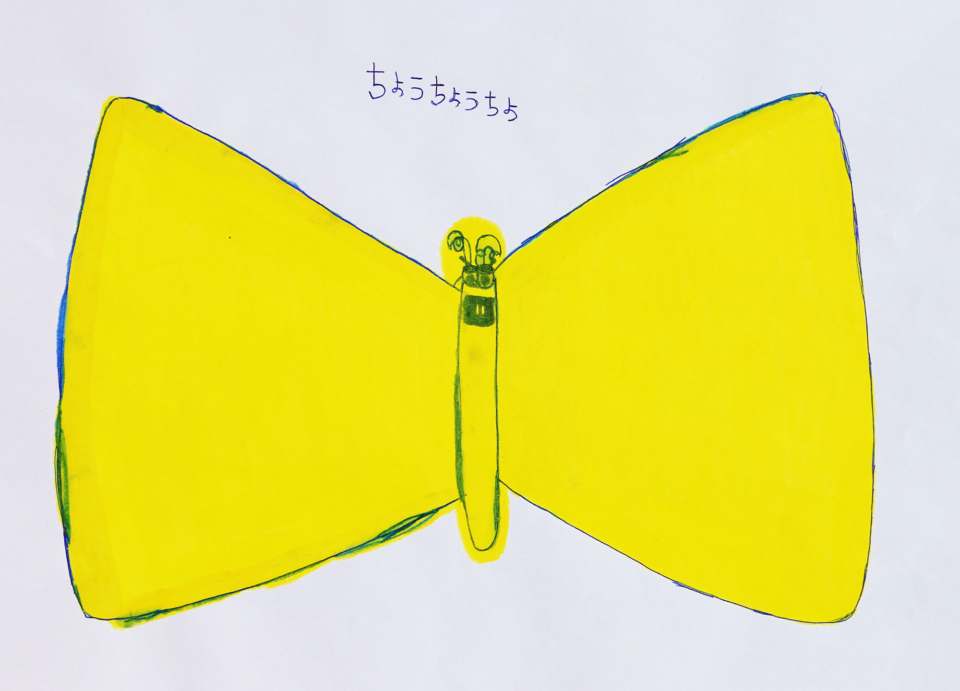

ATELIER YAMANAMI, home to six groups. In one of these, Atelier Korobokkur, members gain experience with a variety of artistic endeavors, centered around clay modeling and drawings.

Studio Cotton, in contrast to Atelier Korobokkur with its mostly male members, is composed entirely of women, from the members to the staff. Every day, while engaged in artistic endeavors like embroidery, sashiko (traditional Japanese quilting), weaving, and painting, they have lively girl talks.

The many outside visitors who come to look at the member’s artwork in Gallery gufguf, or have tea and eat lunch at Café hughug, give the whole facility a free, open atmosphere.

I visited the art-oriented welfare facility ATELIER YAMANAMI, which is located in Konan Town, on the border between the Shiga and Mie prefectures. Currently, 81 artists (members), who are autistic or have intellectual disability, attend the facility and engage in a variety of artistic activities with the 22 staff members. It is an environment that seeks to honor the desires of each and every one of its members, with staff members figuring out how each of them want to spend their day, whether it be going on walks, collecting recycle paper, making desserts, playing sports, or waiting on customers at the café inside of the facility.

One Member’s Smile Changes the Facility

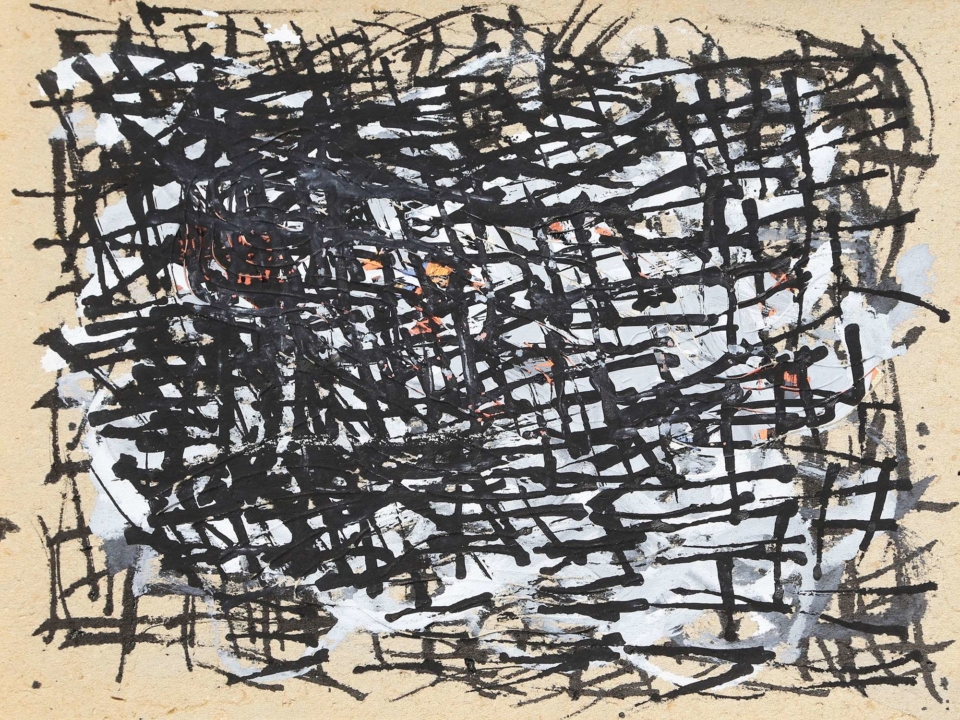

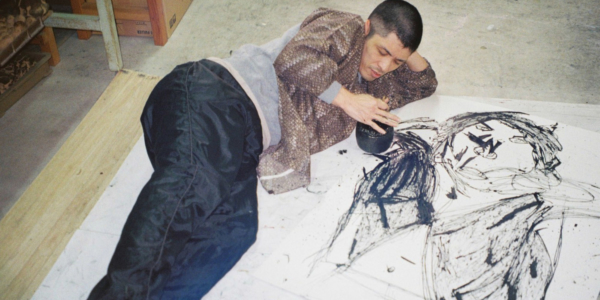

One member sews buttons all over a cloth of their favorite color, then balls it up and sews it together into a spherical shape. Another methodically pokes holes, a set distance apart, into a lump of clay using a chopstick. Yet another, lying down and propped up on one elbow, draws people with India ink and a disposable wooden chopstick. Having caught glimpses of their art, which seemed like the direct expression a desire bubbling inside, I found myself thinking of them in terms of the everyday lives of ancient people. Art as a way of life—I feel that this exists at ATELIER YAMANAMI.

“We as staff members work every day to get members as close as possible to a lifestyle that feels natural and comfortable for them. The art is a result of this, and not the goal. So I still think, personally, that I don’t really know how much artistic value their works actually have. A human being draws a picture. The picture is very mysterious and captivating. It just so happens that this human being also has an intellectual disability. Here is an interesting person who is sharply focused on one thing and who continues to do this one thing. That’s what I want the world to know. It’s with this sentiment that I began to send their pieces out into society, and there, they were discovered by people who saw artistic value in them,” says Masato Yamashita.

Masato Yamashita, facility director, who tells me he previously had no interest in welfare or art, became a certified care worker here because his friend was an employee at Yamanami Welfare Workshop.

In 1989, Mr. Yamashita began working as a certified care worker at Yamanami Welfare Workshop, which got its start in 1986 as a workshop for the three people in the day care center. Currently, as ATELIER YAMANAMI’s facility director, his days are intimately intertwined with that of the facility’s members. When Mr. Yamashita first began working here, the Yamanami Welfare Workshop held as its most important goal the financial independence of people with disabilities, and had organized everyone to work the same jobs in the same space. The change in policy that led to it becoming an artistic facility that honors individuality was sparked by the smile of one member.

“At the time, a man named Keigo Mitsui had come to ATELIER YAMANAMI. Mr. Mitsui had a severe disability, so he couldn’t really tell us what he was thinking in his own words. So he was doing what we asked him to, methodically going through these jobs, until one day during lunch-time he picked up a scrap of memo paper, and started drawing something on it with a pencil he found nearby. His facial expression as he did this was so happy, so joyful. Even though he’d been with us for over a year, it was the first time I’d seen his face like that. I thought to myself—if they have the potential to look this happy, this joyful, then what is the point of them doing jobs every day that can’t get that out of them? Ever since, I began to think about how to make this workshop a place where each and every member could do what they truly wanted to do. Since then, we began to have everyone experience a variety of things. Out of the things he tried, Mr. Mitsui looked the happiest with lively smile when he was touching clay or drawing a picture.”

This experience became the driving force for the creation of Atelier Korobokkur, a place where members gather to create mainly clay modeling and drawings. Six activity spaces were set up within the workshop as places where each member’s individuality could be channeled and given room to bloom. The pieces that accumulated day by day in each of these spaces were discovered in 1994 by Able Art01 advocate Yasuo Harima, who created a foundation for wider societal recognition.

“When we first began doing these artistic activities at ATELIER YAMANAMI, it was difficult for us to turn the pieces into something of value in society, not to mention the fact that the activities themselves didn’t get any attention. Some people were critical, saying this whole thing was meaningless, but I kept coming back to the fact that we only get one life to live, and in the end I think they should do what they want to do. It was during this time of great internal conflict that Mr. Harima discovered the value in their activities, which paved the way for even more activities.”

Recognition for their art works grew gradually as a result of this progression and within a four-year period, Gallery gufguf, currently attached to ATELIER YAMANAMI, has now become a place visited by over 10,000 people from all over the country. At the same time, their pieces have received much praise in both domestic and international museums and art galleries, with some even stored in world-famous collections like the “Collection de l’Art Brut” in Switzerland, “collection abcd” in France, the “Cavin-Morris Gallery” in the U.S., and “The Museum of Everything” in the U.K.

Gallery gufguf hosts four exhibitions a year, displaying pieces not only by the artists at ATELIER YAMANAMI, but also by domestic and international artists.

“I don’t think it’s a good thing for welfare to start and end in welfare facilities. That’s why, if having professionals collaborate with the members as equals allows the charm of the works to be conveyed properly, I’d want to work with them as much as possible and spread the word. What’s important is that their works be evaluated not as the work of people with disabilities, but as art. That means that they are involved in society as individuals, and that really makes me happy.”

Even now that the facility has garnered worldwide attention, none of the staff members at ATELIER YAMANAMI, Mr. Yamashita included, have received any professional artistic training. They also refrain, of course, from providing input and participating in the members’ artistic expression. They focus instead on maintaining the kind of spaces and atmosphere that encourage them to draw. This is because of one of Mr. Yamashita’s fundamental policies, one that he keeps close to his heart at all times.

“No matter how much praise their works receive in society, if they say they don’t want to create any more, then they don’t have to.”

20 Years of Holding and Gazing at Ramen Packages

As I sit sipping tea at Café hughug, which adjoins Gallery gufguf, I see a woman with a short-cut hair in a bright pink sweatshirt coming towards me. Clutched in her hands, which are held up in front of her face, is some kind of package which I do not recognize at first, but as she gets closer I recognize it as a “Sapporo Ichiban” instant ramen package. Her name is Mihoko Sakai—one of the members. Ms. Sakai, who has spent 20 years gazing at ramen packages, has come to Café hughug to have some tea.

“Body temperature, appetite, the expression in their eyes—we as staff members have to sense the members’ needs and wishes in a variety of situations every day. You could say Ms. Sakai, who never lets go of her ramen packages, is the epitome of this kind of process. I personally just couldn’t help but wonder, ‘what are you doing, holding something like that forever?’ And so I tried a lot of things, like taking the bag from her and handing her a pen, but she’d become frustrated and unstable. Finally I gave up, thinking that if holding a ramen package is what relaxes her, then she can keep holding it for as long as she wants.”

Mihoko Sakai, who as long as she is awake, always has a ramen package in her hands.

Ms. Sakai holds the Sapporo Ichiban package and continually feels it in her hands, as if checking the shape of the dried noodles inside. Once she has “used up” the ramen given to her by her mother (when exactly a package is used up, only she knows), she exchanges it with a new one. Because Ms. Sakai never actually eats this ramen, ATELIER YAMANAMI stores all of the used up Sapporo Ichiban packages on a shelf, as art pieces.

People are diverse. What is correct for me might not be correct for someone else. But to say: “Well, we’re all diverse” and sweep the details under the rug feels wrong, like a premature end to the thought process. You and I are different. However while being different, wanting to know you better despite that, and communicating with you, isn’t that the means to get to a world where we can live amongst true diversity? My time at ATELIER YAMANAMI offered me this truer sort of experience.

“I said before that I didn’t really know whether their works have artistic value, but maybe it’s that I admire and feel for each of them far too much that I can’t to look at their works in an objective way.”

Their artworks, which are not derived from artistic techniques or methodologies, do not convey messages in and of themselves. Consequently, the expression of the pieces changes to how we as viewers receive the work, and what we feel from it. How we feel is how we live. Through these artworks, I felt as if the way we live our lives was being called into question.

Information

ATELIER YAMANAMI

Address: 872 Konancho Kazuraki Koka Shiga 520-3321 Japan

Tel : 0748-86-0334

http://a-yamanami.jp/